Article |

|||||||||||||||

Consumers and the Proposal for an Optional Common European Sales Law – No Roads Lead to Rome? [ Volume 2 – 2012 ] |

|||||||||||||||

19 June 2012 |

|||||||||||||||

| FILED UNDER COMMON EUROPEAN SALES LAW, EUROPEAN LAW, SALES LAW | |||||||||||||||

| ( Stefan WRBKA ) PDF download | |||||||||||||||

1. Introduction |

|||||||||||||||

The Proposal for a Regulation on a Common European Sales Law[i] (hereinafter Proposal), which aims at aligning the legal framework for cross-border B2C relationships via an alternative, fully harmonized pan-European sales law regime at the national level[ii], has further intensified the long running debate on the interplay between European sales and consumer law. Numerous scholars, including myself, have been publishing on the Common European Sales Law (hereinafter CESL). Most contributions so far have focused on fundamental issues such as the legal basis of the CESL[iii] and/or its legal classification.[iv] Others have focused on more general issues, such as the necessity for and suitability of the proposed CESL[v]. |

|||||||||||||||

One other, so far rather less considered, issue is the interplay between the CESL and the Rome I Regulation (hereinafter Rome I), especially when it comes to Article 6 of the latter. The European Commission (hereinafter Commission) as well as most contributors who have touched upon this issue, share the opinion that Article 6 Rome I would lose its importance for consumers with a habitual residence in a EU Member State (hereinafter Member State)[vi] if the CESL were adopted.[vii] The question, however, is whether or not that really is the case. This paper therefore aims to analyze the relationship between the CESL and Article 6 Rome I.[viii] It will start by explaining the background and highlighting some core elements of the Proposal. The paper will then continue with a brief analysis of the legal nature of the CESL and an explanation of the importance of the discussion surrounding that issue. It concludes with a more detailed analysis of the CESL in the context of Article 6 Rome I. |

|||||||||||||||

2. Background and Core Elements of the Proposal on a Common European Sales Law2.1. Background and Rationale of the Proposal |

|||||||||||||||

Compared to the time it took European consumer law to evolve, the actual drafting process of the Proposal was a very fast one. It took the European Union (hereinafter EU) and its predecessors nearly three decades from the first explicit references to consumer protection to come up with the idea of elaborating a code on general and consumer contract law, the Common Frame of Reference (hereinafter CFR) [ix]. The actual drafting of that legal framework, which in the end was named the Common European Sales Law (and not CFR), however, only took less than two years. Shortly after the presentation of the Draft Common Frame of Reference (hereinafter DCFR)[x], which in contrast to the CESL/CFR was not a political[xi] document, but rather an extensive research paper funded by the Commission, the Commission installed the Expert Group on a Common Frame of Reference (hereinafter Expert Group)[xii] in April 2010. Already on October 11, 2011 the Commission was able to present the result, the Expert Group’s draft of the CESL as core part of the Proposal. Although one might argue that the CESL eventually builds on the unbinding Principles, Definitions and Model Rules of the DCFR, one must recognize that the Proposal takes the issue to the next level: based on option 6 of the 2010 Green Paper on Policy Options for Progress towards a European Contract Law for Consumers and Businesses (hereinafter, 2010 Green Paper)[xiii] it would create a parallel sales law regime (inter alia) directly applicable to cross-border consumer contracts.[xiv] |

|||||||||||||||

In its Explanatory Memorandum on the Proposal for a Regulation on the European Parliament and of the Council on a Common European Sales Law (hereinafter Explanatory Memorandum) [xv] the Commission tries to convince the readers of the Proposal of the necessity of a pan-European contract law tool for cross-border transactions. With respect to B2C cases the Commission bases its arguments mainly on the outcome of the 2011 Eurobarometer survey “European Contract Law in Consumer Transactions” (hereinafter, B2C survey), in which businesses were asked about the detrimental impact of various law and non-law related factors on cross-border trade. [xvi] International contract law related questions scored very high in the list of international trade impediments, with the “[d]ifficulty in finding out about the provisions of a foreign contract law” and “[t]he need to adapt and comply with different consumer protection rules in … foreign contract laws” ranking first and third respectively.[xvii] |

|||||||||||||||

The Commission copied the main contract law related obstacles identified in the B2C survey nearly word-for-word into the Explanatory Memorandum, which starts as follows: |

|||||||||||||||

Differences in contract law between Member States hinder traders and consumers who want to engage in cross-border trade within the internal market. The obstacles which stem from these differences dissuade traders, small and medium-sized enterprises (SME) in particular, from entering cross border trade or expanding to new Member States’ markets. Consumers are hindered from accessing products offered by traders in other Member States. … The need for traders to adapt to the different national contract laws that may apply in crossborder dealings makes cross-border trade more complex and costly compared to domestic trade … .[xviii] |

|||||||||||||||

After a short description of potential extra costs for businesses in cross-border cases the Commission goes on by referring to Article 6 Rome I as follows: |

|||||||||||||||

In cross-border transactions between a business and a consumer, contract law related transaction costs and legal obstacles stemming from differences between different national mandatory consumer protection rules have a significant impact. Pursuant to Article 6 of Regulation 593/2008 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 June 2008 on the law applicable to contractual obligations (Rome I), whenever a business directs its activities to consumers in another Member State, it has to comply with the contract law of that Member State. In cases where another applicable law has been chosen by the parties and where the mandatory consumer protection provisions of the Member State of the consumer provide a higher level of protection, these mandatory rules of the consumer’s law need to be respected.[xix] |

|||||||||||||||

It is worth noting that the wording of this statement illustrates the position of the Commission towards Article 6 Rome I. The Commission does not stress the importance of this provision for the protection of consumers in cross-border cases residing in a Member State with a comparatively high standard of consumer protection, but rather uses Article 6 Rome I as an argument for the Proposal, claiming that due to the necessity for businesses to comply with foreign legal standards, cross-border trade cannot advance as wished by the Commission or business interest groups. In June 2011, Viviane Reding, the EU Justice Commissioner, in addition stressed that the diversity of national sales laws was not only an economic or legal issue claiming that “[t]he fact that Europe has more than 27 different legal systems for contractual transactions is … a formidable political [emphasis added] challenge for Europe’s single market”[xx]. In other words, in the opinion of the Commission the CESL shall ultimately benefit both businesses and consumers who want to get involved in cross-border transactions and shall ultimately enhance the Internal Market (even if that would mean that consumers might lose the protection of their traditional, domestic sales law regime). |

|||||||||||||||

2.2. Basic Structure and Important Elements of the Proposal |

|||||||||||||||

The Proposal consists basically of three elements: the Regulation on a Common European Sales Law (hereinafter Sales Law Regulation) and two annexes: Annex I, the CESL, and Annex II containing the Standard Information Notice, a mandatory summary of consumers’ contractual rights. While the main part of the Sales Law Regulation contains general, administrative provisions including a catalogue of definitions, the CESL, introduces substantive sales law rules in 186 articles. |

|||||||||||||||

The CESL distinguishes between contracts for goods and service contracts and basically applies only to the first of these two categories: Article 5 Sales Law Regulation determines sales contracts, “digital content” contracts and “related service contracts” [i.e. the only service contract element in the CESL] as the three contract divisions which would fall under the CESL regime.[xxi] As far as B2C transactions are concerned, the CESL was primarily drafted for cross-border cases (Article 4 Sales Law Regulation). This is the logical consequence of the results of the B2C survey, which identified contract law related issues as the main obstacle for cross border sales.[xxii] While the CESL was thus drafted for international B2C transactions in the first place, Article 13 (a) Sales Law Regulation allows Member States to opt for the application of the CESL regime also with regard to pure domestic cases. |

|||||||||||||||

A practically important characteristic of the CESL is to be found in Article 3 in combination with Article 8 Sales Law Regulation: the Commission designed the CESL as an optional instrument, i.e. as a sales law regime which can be chosen by the parties instead of the traditional domestic sales rules. Article 3 Sales Law Regulation provides that “[t]he parties may agree that the Common European Sales Law governs their cross-border contracts for the sale of goods, for the supply of digital content and for the provision of related services” and Article 8 Sales Law Regulation contains the requirements for a party agreement which is necessary in order to make the CESL applicable. As far as B2C cases are concerned, it is required that “the consumer’s consent is given by an explicit statement which is separate from the statement indicating the agreement to conclude a contract”[xxiii]. |

|||||||||||||||

One unsatisfactory aspect of the CESL is to be found in its lacunarity. As the CESL does not cover every potentially important aspect of a sales transaction, there is still the need for traditional rules (outside of the scope of material application of the CESL) which would be additionally applicable in a respective case. Potentially decisive issues such as legal capacity, representation or legal personality, for example,[xxiv] are not covered by the CESL and would be regulated by the traditional domestic regime applicable in any particular case. An explanation for the lacunarity might be that the Expert Group did not have enough time to deal with these matters.[xxv] However, considering that the ultimate aim was to create a harmonized new sales regime for cross-border sales contracts, it is a pity that several important areas are not covered by the CESL draft. The time perspective becomes even more critical if one compares the current CESL draft, presented by the Commission in October 2011, with an older version, presented by the Expert Group as basis for discussion at an academic conference co-hosted by the Centre for European Private Law[xxvi] and the Study Centre for Consumer Law[xxvii] in June 2011 (i.e. only 15 months after the instalment of the Expert Group)[xxviii]. Instead of having added additional rules (on the unregulated areas) between the presentation of the conference draft in June 2011 and the current draft in October 2011, the number of provisions in the CESL draft was cut by three, from 189 to 186. In this respect and also due to the fact that the CESL is “only” an optional device, Article 1 (2) Sales Law Regulation might be misleading when it says that the Sales Law Regulation “enables traders to rely on a common set of rules and use the same contract terms for all their cross-border transactions thereby reducing unnecessary costs while providing a high degree of legal certainty”. Businesses could only fully rely on a comprehensive and all-embracing set of rules if all their B2C transactions fell under the exclusive applicability of the CESL and did not touch on legal issues which are left unregulated by the CESL. This of course is clearly an illusion. |

|||||||||||||||

Also of practical importance – and one of the justifications for this paper – is another statement of the Commission that pursuant to Article 1 (3) Sales Law Regulation the CESL would “ensure a high level of consumer protection”[xxix]. In the Explanatory Memorandum the Commission added that “the level of protection of these mandatory provisions is equal or higher than the current acquis”.[xxx] This “high level of consumer protection” is confirmed even by otherwise more critical voices. Reinhard Zimmermann, for example praises the Proposal for having tried to adopt the “European-wide consumer friendliest solutions for each potential individual problem”[xxxi]. Giesela Rühl concludes that due to an alleged high level of consumer protection enshrined in the CESL draft, the “[a]pplication of Article 6 (2) Rome I-Regulation, therefore, is not necessary to protect consumers against a choice of the CESL”[xxxii]. |

|||||||||||||||

But is this really true? Is the offered consumer protection standard really skyrocketing that high? One must not overlook the fact that there are certainly areas in which the CESL does not meet the same high standards of some traditional domestic provisions. Later in her paper even Rühl is forced to admit that “… while it is true that the CESL exceeds – on average – the consumer protection standard offered by the member states it does not offer more protection in every single case”[xxxiii]. The Commission itself, this time in Recital 11 Sales Law Regulation, also somehow mitigates its overwhelming appraisal of the CESL by saying that the new regime would “maintain or improve the level of protection that consumers enjoy under Union [emphasis added; Note: not national] consumer law.”[xxxiv] One example, where traditional domestic rules go beyond the draft rules of the CESL, is to be found in the Austrian rules of reversing the burden of proof in B2C cases: while Paragraph 6 (1) lit. 11 KSchG absolutely forbids a contractual clause whereby the “burden of proof is imposed on the consumer which does not by law fall upon him”, this issue falls only under the grey listof Art. 85 CESL instead of the blacklist of Art. 84 CESL.[xxxv] And even if the step from a black list to a grey list regulation might be only a minor step backwards, it is nevertheless a step backwards – and not the only one for sure. |

|||||||||||||||

One thus has to understand that the CESL in its current wording might lead to an improvement in average, but does not necessarily lead to an improvement of consumer rights in every single case, especially not in Member States with high domestic consumer protection standards. This is exactly the reason why one should take a closer look at the interplay between the CESL and Article 6 Rome I, as will be done further below.[xxxvi] |

|||||||||||||||

3. Legal Nature of the Proposed Common European Sales Law3.1. General Remarks and Background of the Discussion |

|||||||||||||||

One question that several academics have dealt with is the question of the legal nature of the proposed CESL.[xxxvii] This question is quite important since the respective classification of the CESL has implications for the applicability of Rome I. |

|||||||||||||||

In this respect it is important to distinguish between different models, of which the two most widely discussed are commonly called the “2nd regime” and the “28th regime”, two terms which have dominated the latest discussion.[xxxviii] The term “2nd regime” refers to a set of legal provisions which stands as a parallel, alternative mechanism at the same national level as traditional domestic rules. On the other hand the term “28th regime” classifies the CESL as a set of contract law rules which adds a new regime to the already existing sales laws of the current 27 Member States. It is considered to be an optional, yet non-domestic tool. The main rationale behind this idea is to be found in the legal process of establishing the CESL: it is not the national legislator, but the legislator at the EU level who would enact the CESL.[xxxix] Thus one might be tempted to argue that the CESL is in fact not a 2nd national law within each Member State, but that it would stand at the same level together with all 27 national sales laws of the EU, adding a 28th regime.[xl] |

|||||||||||||||

According to the Commission the “Proposal provides for the establishment of a Common European Sales Law. It harmonises the national contract laws of the Member States not by requiring amendments to the preexisting national contract law, but by creating within (note: emphasis added) each Member State’s national law a second contract law regime”[xli], i.e. the CESL thus shall be treated as national law, free-standing next to the traditional national sales law regimes at the domestic level. In the opinion of the Commission it thus should be considered as a 2nd regime at the national level, not as a 28th regime. The CESL would leave the traditional sales laws fully untouched, i.e. it would not require Member States to apply a new law which replaces the traditional national sales law. |

|||||||||||||||

But why could it be important to consider the CESL as either a 2nd regime or a 28th regime at all? Let us take a brief look at the two models and their implications for the application of the Rome I framework. |

|||||||||||||||

3.2. The CESL as a 28th Regime? |

|||||||||||||||

Treating the CESL as a free-standing additional sales law mechanism is exactly the opposite of what the Commission favours. The classification of the CESL as a 28th regime would also create several practical problems, among which its interrelationship with Article 3 (1) Rome I, allowing the contractual parties to choose the applicable law, might be the most striking one. The prevailing opinion views non-state laws as not falling under Article 3 (1) Rome I.[xlii] This would still in principle not prevent the contractual parties from incorporating the CESL rules into their contract. According to Recital 13 Rome I the “[Rome I] Regulation does not preclude parties from incorporating by reference into their contract a non-State body of law”. Of course, such incorporation by reference (“materiellrechtliche Verweisung”) would, however, mean that the provisions are overruled by mandatory national provisions, [xliii] something that the Commission clearly wants to avoid. |

|||||||||||||||

Another argument against the 28th regime approach is closely linked to the definition of national and non-national law. This clarification is important, since the Commission’s idea was to circumvent the applicability of the protection offered by Article 6 Rome I via the addition of an optional national sales law.[xliv] It was never intended to grant the parties a choice of law between national and non-national law. With regard to “national” and “non-national” laws, one must not make the mistake of mixing up the legal origin of the law with its legal nature or legal “impact”: every EU regulation is established by the European legislator and not its national counterpart. In this sense it might be regarded as “non-national”. However, every EU regulation is directly applicable within a Member State without the need for implementation into “genuine” national law. If one understands “national” law not as a law which is enacted nationally by the respective domestic legislator (“enactment process”), but rather as a law which is applied at the national level (“application process”), then there is no need to consider the CESL as a non-national tool. Just like any other EU regulation it is nationally applicable in Member States and therefore national law, even though it would be non-nationally established. |

|||||||||||||||

To conclude, one must thus say that classifying the CESL as a 28th regime is neither what the Commission is looking for nor is it actually needed, as we can differentiate between the enactment process and the application process of EU law; even if the first one points in the direction of non-nationality, laws can be national from an applicational point of view. |

|||||||||||||||

3.3. The CESL as a 2nd Regime? |

|||||||||||||||

For the Commission as well as many commentators, especially those who are in favour of the new regime,[xlv] treating the CESL as a 2nd, i.e. alternative and parallel, national sales law at the Member State level is the preferred and most obvious option, as it seems to circumvent a crucial problem that a 28th regime would face: one could – so it is generally believed – render the preferential-law test of Article 6 (2) Rome I useless if parties agreed on the applicability of the CESL, as it harmonizes the sales rules at a pan-European level.[xlvi] |

|||||||||||||||

As shown in the previous subchapter, it is possible to consider the CESL as a 2nd sales law mechanism at the national level, even if its enactment happens at the non-national level.[xlvii] The reason why this issue has been that heavily discussed is solely the fact that installing such a comprehensive regime at the national law level must be considered innovative in the field of consumer law. Yet it would not be the first time that the EU draws on an optional instrument for the purpose of harmonizing national laws: prominent examples such as the Societas Europaea (hereinafter SE)[xlviii] or the Community Trade Mark (hereinafter CTM)[xlix] show that optional legal devices are already used in the EU.[l] But unlike in these cases, the CESL would very likely have a high impact directly on consumers and their economic transactions. This, together with the fact that cross-border consumer transactions are (in many cases) regulated by the Rome I regime, shows the necessity of dealing with the private international law perspective more closely. |

|||||||||||||||

Let us now take a closer look at how the CESL, if enacted in its current wording, and the Rome I Regulation, especially Article 6 Rome I, would interact. Would the latter one lose its importance (at all)? |

|||||||||||||||

4. The Common European Sales Law and Rome I – an Undisputed Relationship in Favour of the CESL?4.1. General Remarks |

|||||||||||||||

The Rome I Regulation is built on the idea of party autonomy. As a general rule, parties are free to submit their contractual rights and duties to the legal regime of a country of their choice.[li] This ideal is stressed by Recital 11 Rome I which states that “[t]he parties’ freedom to choose the applicable law should be one of the cornerstones of the system of conflict-of-law rules in matters of contractual obligations.” However, there are certain areas in which one party might have more bargaining power or more legal knowledge than the other and could easily decide on the applicable law by him- or herself. Especially in cases in which Member States enacted mandatory rules to protect their citizens, it is in the interest of the respective Member State as well as of the residing citizen to vest legal power to the protective, mandatory domestic regime. This is also recognized by several Rome I provisions, of which Article 6 Rome I, applicable in (many) B2C transborder cases, is a prominent example. |

|||||||||||||||

Based on the precondition that the cross-border sale meets the substantial requirements of Article 6 (1) Rome I, the contractual B2C relationship is “governed by the law of the country where the consumer has his habitual residence”. According to Article 6 (2) Rome I the parties may submit the contract under another law, but cannot deprive the consumer of the protection of the mandatory rules of his home country, as it states that “[s]uch a choice may not, however, have the result of depriving the consumer of the protection afforded to him by provisions that cannot be derogated from by agreement by virtue of the law which, in the absence of choice, would have been applicable on the basis of paragraph 1”. |

|||||||||||||||

So far Article 6 Rome I has undeniably played an important role for consumers residing in Member States with a comparatively high standard of consumer protection. This picture might, however, change in the future once and if the CESL becomes reality. |

|||||||||||||||

4.2. Why Do We Have to Care? |

|||||||||||||||

One reason why it is necessary to discuss the interrelationship of the CESL and Rome I is to be found in the assertion of the Commission that the application of the CESL would have the effect that Article 6 (2) Rome I would have “no practical importance for the issues covered by the Common European Sales Law”[lii], as it would introduce a fully harmonized regime, which is the same in every Member State. This has to be seen especially in context with another claim of the Commission, namely that the CESL would “maintain or improve the level of protection that consumers enjoy under Union [emphasis added] consumer law”[liii]. |

|||||||||||||||

There would, of course, not be any practical need to analyze this issue any further if the CESL really kept or improved the national level for consumers in every case. Nobody would have a problem with the CESL if it really overrode traditional national sales law every time it was chosen in such a case. But while it might be true that in many cases – and maybe[liv] also on average – the level of consumer protection would be raised (or at least maintained), this does not mean that this would be true in every single case, as earlier shown.[lv] |

|||||||||||||||

This fact also has to be seen in the context of Article 3 Sales Law Regulation. As explained above, the CESL as an optional instrument is only applicable if the parties opt-in, i.e. choose the CESL as applicable law. This voluntariness does, however, not necessarily mean that consumers have a choice. Nothing in the Proposal guarantees that consumers could conclude a cross-border sales contract based on their traditional national law, if the other party does not agree. Businesses could in fact exercise soft pressure on consumers to agree on the businesses’ preferred law, as businesses could very easily make the acceptance of the CESL a precondition for concluding the contract.[lvi] In this context Jürgen Basedow aptly notes that “[t]he choice between national laws and the optional instrument [note: i.e. the CESL] will lie with businesses exclusively [emphasis added].”[lvii] In other words, the voluntariness of the CESL would only exist on paper, not also in practice. |

|||||||||||||||

This situation, i.e. the businesses’ power to decide on the applicable law in combination with the fact that the CESL would not improve (or at least maintain) the protective consumer standard in every single case, would clearly put high consumer standards in several Member States at risk, especially if in reality “no roads led to (Article 6) Rome”. |

|||||||||||||||

4.3 The Assumption of the Commission |

|||||||||||||||

The Commission is convinced that consumers would not be protected by Article 6 Rome I by choosing the CESL. Unfortunately, none of the commentators has questioned this assumption so far, most likely because at first sight the argument sounds logical: in every Member State the respective CESL would be exactly the same. If chosen, then the consumer would have no disadvantage compared to the CESL of his home country (hereinafter also consumer’s home country), or in other words: the CESL of his home country does not contain any stricter mandatory rules. |

|||||||||||||||

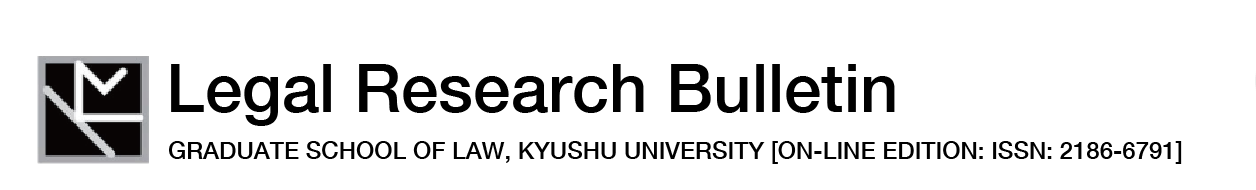

Basically the following four cases are likely to occur, based on the assumption that the contract fulfils the basic requirements of Article 6 Rome I: (1) the parties do not agree on any law; (2) the parties agree (only) on the CESL in general without reference to any Member State’s law; (3) the parties agree on the CESL of the Member State where the business operates from (hereinafter also business’s home country) (note: or any other non-consumer based Member State; to simplify this, we can, however, refer to the business’s home country only); or (4) the parties agree on the CESL of the Member State where the consumer has his habitual residence. Put into a table it could be summarized as follows: |

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

Table 1: The Assumption of the Commission |

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

Let us take a closer look at these four scenarios from the perspective of the Commission’s arguments. |

|||||||||||||||

4.3.2. No Contractual Agreement on the CESL |

|||||||||||||||

This scenario is the only one where the CESL does not play any role. The parties either do not agree on any applicable law; then, pursuant to Article 6 (1) Rome I the traditional sales law of the consumer’s home country is applicable (note: we come to the same practical result if the parties agree on the applicability of the law of the consumer’s home country without any reference to the CESL). Or the parties agree on the applicability of the law of the business’s home country; in this case the contract would be subject to the preferential-law test of Article 6 (2) Rome I (without taking the CESL of the consumer’s home country into consideration).[lviii] |

|||||||||||||||

4.3.3. Agreement on the Applicability of the CESL without Further Reference to Any (National) Law |

|||||||||||||||

If the parties do not agree on the applicable national law, then one needs to decide which Member State’s law regulates the contractual relationship (as not all possible contract related issues are governed by the CESL). |

|||||||||||||||

The answer is to be found in Article 6 (1) Rome I which rules that the contract “shall be governed by the law of the country where the consumer has his habitual residence”. Although Article 6 (1) Rome I principally aims at those cases where the parties do not agree on anything, one could say that it should also apply in this scenario, as the parties do not choose the generally applicable national law. Article 6 (1) Rome I would thus substitute the missing “first step”, namely choosing a national law in general (hereinafter first step). As the CESL of the consumer’s home country is the applicable sales law in this case, there is no room left for a preferential-law test here. |

|||||||||||||||

4.3.4. Agreement on the Applicability of the CESL of the Consumer’s Home Country |

|||||||||||||||

This scenario is more or less the same as the above discussed case. The only difference is to be found in the fact that the parties themselves would also decide about the first step and not leave its determination to Article 6 (1) Rome I. |

|||||||||||||||

Everything else is exactly the same as in the previous subchapter. Again, since the CESL of the consumer’s home country is applicable, no preferential-test would be used. |

|||||||||||||||

4.3.5. Agreement on the Applicability of the CESL of the Business’s Home Country |

|||||||||||||||

Also in the final scenario the parties agree generally on the applicable law. However, unlike in the previous subchapter, the parties would choose the law of the business’s home country (including the CESL). This case might be the practically most important and common scenario as businesses usually tend to favour the legal regime of their own Member State, as they are more familiar with that country’s laws. |

|||||||||||||||

As the CESL of a Member State other than the consumer’s home country would be chosen, one would have to exercise a preferential law test pursuant to Article 6 (2) Rome I. The Commission assumes that this preferential-law test would not lead to the applicability of stricter traditional sales rules: since the CESL is the same in every Member State and since it can be chosen by the parties, there are no stricter mandatory rules in the consumer’s home country. |

|||||||||||||||

4.4. The Actual Consequences for Rome I |

|||||||||||||||

As has already been mentioned, the CESL would neither maintain nor improve the level of consumer protection in all 27 Member States if it were to be adopted in its current draft wording.[lix] This could turn out to be fatal for stricter traditional protective regimes, if the CESL really overrode them, especially since in practice it would be the foreign business to decide on the applicability.[lx] For these Member States one must hope for one of the following three, namely that (1) the protective level of the CESL would eventually be further raised; (2) the legislator would not enact the CESL, or (3) the assumption of the Commission with regard to the Rome I regime would turn out to be false. |

|||||||||||||||

While the first two options are beyond the commentators’ direct control, one should discuss the third possibility in more detail. If the Commission could be proven wrong then one might actually reach a result satisfactory for consumers in every Member State despite a possible enactment of the CESL. |

|||||||||||||||

4.4.2. No Contractual Agreement on the CESL |

|||||||||||||||

This scenario is the least worrisome, as nothing is different from the status quo.[lxi] The CESL would not be applicable, as there would not be a party agreement on its applicability as required by Article 3 Sales Law Regulation. The traditional sales law of the consumer’s home country would be either the directly applicable law or at least would have to be used as the yardstick for a preferential-law test. |

|||||||||||||||

4.4.3. Agreement on the Applicability of the CESL without Further Reference to Any (National) Law |

|||||||||||||||

If one understands the CESL as a 2nd regime and not as a 28th, then the assumption of the Commission with regard to this scenario is correct. As Article 6 (1) Rome I would lead to the applicability of the CESL of the consumer’s home country as a partial “law of the country where the consumer has his habitual residence” in the sense of Article 6 (1) Rome I, there is indeed no place for a preferential-law test pursuant to Article 6 (2) Rome I. The assumption of the Commission that consumers would not be protected by their traditional sales law is therefore true.[lxii] |

|||||||||||||||

4.4.4. Agreement on the Applicability of the CESL of the Consumer’s Home Country |

|||||||||||||||

Also in this scenario the assumption of the Commission is correct. This case is more or less identical with the case just mentioned. The CESL of the consumer’s home country would be explicitly chosen and no preferential-law test applied. The only difference is to be seen in the fact that one would not need Article 6 (1) Rome I to clarify the question of which Member State’s CESL would govern the contractual relationship. |

|||||||||||||||

4.4.5. Agreement on the Applicability of the CESL of the Business’s Home Country |

|||||||||||||||

This case is obviously the most interesting one, as it is the most likely one to occur in practice. |

|||||||||||||||

Let us recall what the Commission argues: pursuant to Recital 12 Sales Law Regulation, Article 6 (2) Rome I has “no practical importance for the issues covered by the Common European Sales Law”, as the CESL is the same in every Member State and a preferential-law test would thus not be beneficial for consumers. In other words, the Commission is of the opinion that the yardstick in the preferential-law test under Article 6 (2) Rome I would be the CESL of the consumer’s home country. The main argument for this is the claim that the traditional consumer law of the consumer’s home country could not be regarded as containing any mandatory provision, or to use the wording of Article 6 (2) Rome I, could not be considered as consisting of “provisions that cannot be derogated from by agreement”, as the CESL could always be used instead of the traditional law if the parties agreed on its applicability. Stefan Leible argues similarly saying that (note: in a cross border case where the consumer habitually resides in Germany) “even if German law were applicable [via the preferential-law test], the [German] CESL could have been chosen.”[lxiii] In this case, according to Leible, one would have to use the German CESL, and not the German traditional sales law, as a yardstick in the preferential-law test. As both CESLs are the same, the consumer could not enjoy any “better” protection by his or her home country. At first glance this might sound convincing, but this view has its flaws. |

|||||||||||||||

Of course, for the preferential-law test we need to determine the yardstick. One has to do that in two steps: first, one has to find “the law, which in absence of choice, would have been applicable on the basis of paragraph 1” and, as a second step, one needs to look for mandatory provisions within that law. The first step is the easier one. If there were no choice, then pursuant to Article 6 (1) Rome I the law of the consumer’s home country would be applicable. But for finding the yardstick one needs to go one step further and ask whether that country’s law contains mandatory provisions. |

|||||||||||||||

First, it is too easy and actually wrong to argue that, as the parties could agree on the CESL anyway and circumvent the protection offered by the traditional sales law, there were no mandatory provisions in the traditional regime and that the only mandatory rules could be found in the CESL. If one does not understand the traditional sales law as containing mandatory rules in the sense of Article 6 (1) Rome I, then one must also not understand that country’s CESL as containing mandatory rules. The parties can very easily avoid the applicability of the CESL by agreeing on the applicability of the traditional sales law of the consumer’s home country instead. Actually they can avoid the applicability of the CESL even more easily, namely by not agreeing on any sales law regime at all. In both cases the traditional sales law regime would be applicable, as the CESL is only an alternative regime requiring an explicit agreement. |

|||||||||||||||

Second, as the CESL is only an alternative, 2nd (ranked) regime, one has to analyze whether the traditional sales law, being the 1st (ranked) regime, really does not contain any mandatory provisions. Actually, (genuinely) mandatory rules of the traditional sales law, taken individually and not as a “total package”, are still mandatory, even if the CESL were enacted. The only way to get rid of them is to fully replace the traditional sales law by the CESL of that country. The provisions of the traditional sales law, taken individually, are, however, clearly “provisions that cannot be derogated from by agreement by virtue of the law which, in the absence of choice, would have been applicable on the basis of paragraph 1” and thus are mandatory provisions. Having the possibility to replace the whole set of traditional sales law rules by the CESL does not mean that single provisions of the traditional sales law are not mandatory. Nobody can tell if parties in general (note: the yardstick in the preferential-law test should be an objective and not a concrete one), fully aware of the consequences that such a choice would mean for the concrete issues being the subject of the litigation, would replace all provisions of the traditional sales law by the CESL regime, especially if that would lead to other, unwanted consequences. We thus can say that since one can depart from the traditional sales law only by choosing a totally separated regime, namely the CESL as a total package, rules of the traditional sales law taken individually are still mandatory in the sense of Article 6 (1) Rome I. |

|||||||||||||||

Even if one tried to deny this fact by arguing that the parties agreed on the applicability of the CESL in the concrete case (and thus tried to use a concrete rather than an objective yardstick), this would not necessarily lead to a different result. “In the absence of choice” should be understood as “having no agreement at all”. One would have to read the contract without the reference to the business’s home country and the CESL as being an integral part of that choice. There is no indication that the parties would have agreed on the CESL if the law of the business’s home country were not chosen. Nothing tells us whether the consumer willingly, i.e. freely, accepted the CESL or whether he or she was even aware of the consequences the CESL would mean for the contractual relationship. It should rather be assumed that the consumer would have wanted to enjoy the best possible protection. And in case that protection were offered by the traditional sales law of his or her home country, it would rather be that one which he or she would agree on, if he or she had the free choice or at least bargaining power. |

|||||||||||||||

One can thus conclude that the traditional sales law of the consumer’s home country contains mandatory rules and that it enjoys preference over the CESL as the latter is only an alternative regime. It is thus the traditional sales law of the consumer’s home country, not that country’s CESL which should be used as a yardstick in the preferential-law test pursuant to Article 6 (2) Rome I. This is also in line with the rationale of Article 6 Rome I which seeks to grant the best possible protection to consumers, something which can only be done if the actual choice of the CESL is compared to an objective yardstick, the traditional sales law of the consumer’s home country. |

|||||||||||||||

There is another good reason why the traditional sales law of the consumer’s home country, and not that country’s CESL, should be used as a yardstick: the basic rationale of Article 6 Rome I and its preferential-law test is that consumers shopping across borders should enjoy (at least) the same protective standard as they would at a domestic level. This view is the basic understanding, expressed for example by Bettina Heiderhoff who argues that “[t]he applicability of a foreign law [in cross-border cases] is … undesirable, as it could deprive the consumer of his or her rights in certain situations”.[lxiv] Gralf-Peter Calliess summarizes the rationale of Article 6 Rome I as follows: |

|||||||||||||||

“[w]here the national legislator aims at protecting consumers from abuse of freedom of contract which may result from an inequality of bargaining power between the consumers and professionals, and therefore enacts mandatory consumer contract regulations which cannot be derogated from by agreement, the thus created substantive consumer rights should be protected as well in an international situation”.[lxv] |

|||||||||||||||

The consumers’ fear of being possibly exposed to weaker legal protection is also indirectly recognized by the Commission in the Explanatory Memorandum, when it says that “[o]ne of the important reasons for this situation [note: the assumption that consumers are reluctant to shop across borders] is that, because of the differences of national laws consumers are often uncertain about their rights in cross-border situations”[lxvi] or to put it in other words, “consumers are uncertain whether their rights in cross-border situations can be protected in the same way as domestically”. |

|||||||||||||||

So, what is the protective standard at the national level? Generally, Member States would apply only the traditional sales law in domestic cases, as the CESL is primarily aimed at cross-border sales. Of course, pursuant to Article 13 (a) Sales Law Regulation Member States have the option to adopt the CESL rules also for purely domestic cases. But as shown above,[lxvii] the problem is that the CESL could put consumers in a worse position compared to the already existing domestic traditional sales law rules. In particular Member States with higher protective standards are thus very unlikely to install a second regime, i.e. the CESL, for domestic cases or even replace the traditional, well-established national regime if that leads to a worse treatment of consumers shopping domestically. In other words, in purely domestic cases we would still have only one sales law regime – the traditional sales law containing mandatory rules to protect consumers on the domestic market. |

|||||||||||||||

This has the following implications for our case: if one wants consumers who shop across borders to enjoy the same legal standard as they do when shopping domestically, then one may only use the traditional sales law of the respective Member State as a yardstick in the sense of Article 6 (2) Rome I. If there is only the traditional sales law available for domestic cases, then one must make sure that (at least) the same level is maintained in cross-border sales. Using the traditional sales law of the consumer’s home country as a yardstick is also compatible with cases where that country’s traditional protection is weaker than what is offered by the CESL, as the preferential-law test would not lead to a supersession of the CESL by weaker traditional rules and thus the higher standard of the CESL can be applied in the particular case. This is also in line with the before mentioned argument of the Commission, which wants to strengthen the consumers’ trust in the legal regime which governs cross-border sales. Putting the consumers in a worse legal situation in cross-border cases compared to purely domestic cases is certainly not what the Commission intends and would clearly be counter-productive. Taking this approach thus guarantees that consumers shopping across borders can enjoy the best possible protection and at least the same standards as in purely domestic cases. |

|||||||||||||||

This understanding also helps in the following: the Commission chose the legal form of an optional instrument over a “genuine” full harmonization tool replacing traditional sales laws, as it would be the “lesser evil” and would not only be more likely to be politically acceptable, but might also be more easily accepted by the ECJ.[lxviii] The Commission, however, does not provide for any mechanism within the Sales Law Regulation which guarantees the free choice of the consumer. In keeping with the motto take it or leave it the choice of the applicable law would be made by the professional only.[lxix] The Commission might thus actually reach the same results as it would have done if it had chosen option 6 of the Green Paper on Policy Options for Progress towards a European Contract Law for Consumers and Businesses[lxx], i.e. if it had introduced a “Regulation establishing a European Contract Law” or as Geraint Howells puts it, the CESL might result in “de facto achieving in practical terms … maximal harmonisation”. But that is exactly what the Commission wanted to avoid.[lxxi] Using the traditional sales law of the consumer’s home country as a yardstick in the preferential-law test could easily prevent this from happening in the practically most likely scenario, namely in the case that the professional pushes for the law (including the CESL) of his or her home country. |

|||||||||||||||

5. Conclusion |

|||||||||||||||

As we have seen, the possible adoption of the CESL could lead to uncertainties with regard to the application of the “correct” sales law. If one follows the assumption of the Commission, consumers with a habitual residence in a Member State with a higher traditional protective standard would be treated less favourably. But the Commission’s way of interpreting the Rome I regime, especially the preferential-law test of Article 6 (2) Rome I, is not the only way to understand the interrelationship between the CESL and Rome I. Moreover, it is not even the correct way. Taking the rationale of Rome I, the practically non-existing consumers’ choice between the CESL and traditional sales laws as well as the false promise of the Commission that the CESL would necessarily improve the situation for consumers into consideration, one has to come to a different conclusion – at least in the practically most likely case, namely that the contract is based on the law of the business’s home country. |

|||||||||||||||

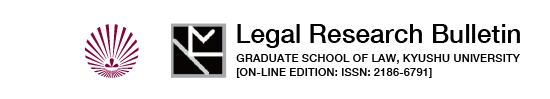

One still has to hope for an actual revision of the CESL before its enactment. But interpreting Article 6 Rome I in a consumer-friendlier way can at least help in the practically most relevant case, i.e. if the CESL of the business’s home country is chosen. The following table illustrates this: |

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

Table 2: Comparison of the Assumption of the Commission and Reality |

|||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

Eventually, even the Commission should be pleased with this: for those Member States where the traditional protective standards are weaker than in the CESL, the CESL might be an improvement. At the same time, consumers habitually residing in Member States with a higher consumer protection level could in many cases still enjoy the same standard as when shopping domestically. This would clearly be a win-win situation for every consumer. |

|||||||||||||||

| * Associate Professor at Graduate School of Law and International Education Center, Kyushu University, Japan; LL.M. (Kyushu University), Mag. iur. and Dr. iur. (University of Vienna). |

[i] Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on a Common European Sales Law, October 11, 2011, COM(2011) 635 final. |

[ii] For the discussion of the legal nature of the proposed Common European Sales Law see e.g. chapter 3 of this paper and the literature mentioned in infra note 6 for more details. |

[iii] See e.g. Horst Eidenmüller et al., Der Vorschlag für eine Verordnung über ein Gemeinsames Europäisches Kaufrecht: Defizite der neuesten Textstufe des europäischen Vertragsrechts, Juristenzeitung 269, 274 (2012); Max Planck Institute for Comparative and International Private Law, Policy Options for Progress Towards a European Contract Law – Comments on the issues raised in the Green Paper from the Commission of 1 July 2010, COM(2010) 348 final, 75 RabelsZ 371, 386-96; Johannes Stabentheiner, Der Entwurf für ein Gemeinsames Europäisches Kaufrecht – Charakteristika und rechtspolitische Aspekte, 2 wbl 61, 65 (2012); Reinhard Zimmermann, Perspektiven des künftigen österreichischen und europäischen Zivilrechts, 134 JBl 2, 19 (2012); Karl Riesenhuber, Der Vorschlag für ein “Gemeinsames Europäisches Kaufrecht” – Kompetenz,Subsidiarität, Verhältnismäßigkeit, Stellungnahme für den Rechtsausschuss des Deutschen Bundestages 1, 5-10 (February 2, 2012), available at http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1998134 (visited May 19, 2012); Gary Low, A Numbers Game – The Legal Basis for an Optional Instrument in European Contract Law, 2 Maastricht European Private Law Institute Working Paper 1 (January 2012), available at http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1991070 (visited May 19, 2012). |

| [iv] See e.g. Eidenmüller et al., supra note 3, at 269-70; Max Planck Institute for Comparative and International Private Law, supra note 3, at 400-2; Simon Whittaker, The Optional Instrument of European Contract Law and Freedom of Contract, 3 ERCL 371, 383-5 (2001); Giesela Rühl, The Common European Sales Law – 28th Regime, 2nd Regime or 1st Regime, 5 Maastricht European Private Law Institute Working Paper 3 (March 19, 2012), available at http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2025879 (visited May 19, 2012); Martijn W. Hesselink, How to Opt into the Common European Sales Law – Brief Comments on the Commission’s Proposal for a Regulation, Centre for the Study of European Contract Law Working Paper Series No. 2011-15 1 (2011), available at http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1950107 (visited May 19, 2012); Dirk Staudenmayer, Der Kommissionsvorschlag für eine Verordnung zum Gemeinsamen Europäischen Kaufrecht, 48 NJW 3491, 3494-5 (2011); Helmut Heiss and Noemí Downes, Non-Optional Elements in an Optional European Contract Law. Reflections from a Private International Law Perspective, 5 European Review of Private Law 693, 700-12 (2005); Wulf-Henning Roth, Stellungnahme zum “Vorschlag für eine Verordnung des Europäischen Parlaments und des Rates über ein Gemeinsames Europäisches Kaufrecht, KOM (2011) 635 endg.”, 2-6 (December 8, 2011), available at http://www.bundestag.de/bundestag/ausschuesse17/a06/anhoerungen/archiv/16_Europaeisches_Kaufrecht/04_Stellungnahmen/Stellungnahme_Roth.pdf (visited May 19, 2012). |

[v] See e.g. Stefan Wrbka, The Proposal for an Optional Common European Sales Law – A Step in the Right Direction for Consumer Protection?, EUIJ-Kyushu Review 1, 13-27 (2012); Hans-Werner Micklitz and Norbert Reich, The Commission Proposal for a “Regulation on a Common European Sales Law (CESL)” – Too Broad or Not Broad Enough?, in Hans-Werner Micklitz and Norbert Reich (eds.), The Commission Proposal for a “Regulation on a Common European Sales Law (CESL)” – Too Broad or Not Broad Enough ? / 4 EUI Working Papers Law 1 (2012); Norbert Reich, An Optional Sales Law Instrument for European Businesses and Consumers?, in Micklitz and Reich (eds.), Commission Proposal 68. |

[vi] As the CESL would only be directly applicable in Member States, consumers residing outside of the EU would still automatically benefit from the preferential-law test pursuant to Article 6 (2) Rome I, if the CESL of the business’s home country were chosen and the protective standard of that country were higher. |

[vii] See chapter 4.3 of this paper and the literature presented therein for more details. |

[viii] The reason why the paper focuses on Article 6 Rome I is the fact that it is the central provision of the Rome I Regulation dealing with consumer issues and – as far as I know – has not been analyzed in detail yet. For arguments related to Articles 9 (“ordinary mandatory provisions”) and 21 (“public policy”) Rome I as being the Rome I provisions being possibly affected by the CESL see e.g. European Consumers’ Organisation (BEUC), Towards a European Contract law for Consumers and Business? Public Consultation on the Commission’s Green paper on European Contract Law. BEUC’s response, 13 available at http://ec.europa.eu/justice/news/consulting_public/0052/contributions/120_en.pdf (visited May 19, 2012). |

[ix] See the first explicit references of the Council to consumer law issues in Council Resolution of 14 April 1975 on a preliminary programme of the European Economic Community for a consumer protection and information policy, OJ 1975 No. C92, followed by Council Resolution of 19 May 1981 on a second programme of the European Economic Community for a consumer protection and information policy, OJ 1981 No. C133 and the Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council – A more coherent European contract law – An action plan, March 15, 2003, COM(2003) 68 final. For the difference between the CRD and the DCFR see e.g. Wrbka, supra note 5, at 8. |

[x] The main players in the drafting process of the DCFR, a major intermediate step towards the Proposal, were the European Research Group on Existing EC Private Law of 2002, a research group better known as the Acquis Group, and the Study Group on a European Civil Code. For details on the two research groups and their work see e.g. Wrbka, supra note 5, at 6-9. |

[xi] Study Group on a European Civil Code and the Research Group on EC Private Law (Acquis Group), Principles, Definitions and Model Rules of European Private Law – Draft Common Frame of Reference (DCFR) Outline Edition (2009), at 4. |

[xii] See Commission Decision of 26 April 2010, setting up the Expert Group on a Common Frame of Reference in the area of European contract law, 2010/233/EU. |

[xiii] Green Paper from the Commission on policy options for progress towards a European Contract Law for consumers and businesses, July 1, 2010, COM(2010) 348 final, available at http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=COM:2010:0348:FIN:en:PDF (visited May 19, 2012); for option 6 see its p. 11. |

[xiv] Taking the short drafting process of the draft into consideration one has to agree with the critical voices raised by various scholars such as Hans-Werner Micklitz or Reinhard Zimmermann who commented on the lacunarity of the proposed CESL, arguing that the incompleteness was due to the “extremely tight time schedule”; see e.g. Zimmermann, supra note 3, at 21 or Hans-Werner Micklitz, A “Certain” Future for the Optional Instrument, in Reiner Schulze & Jules Stuyck (eds.), Towards a European Contract Law 181, 181 (2011). |

[xv] European Commission, Explanatory Memorandum to the Proposal for a Regulation on the European Parliament and of the Council on a Common European Sales Law (October 11, 2011) <http://ec.europa.eu/justice/contract/files/common_sales_law/regulation_sales_law_en.pdf> (visited May 19, 2012) |

[xvi] The Gallup Organization, Hungary, European Contract Law in Consumer Transactions. Analytical Report. Flash Eurobarometer 321 (2011) (hereinafter B2C survey) <http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/flash/fl_321_en.pdf> (visited May 19, 2012). See also the parallel survey dealing with B2B transactions: The Gallup Organization, Hungary, European Contract Law in Business-to-business Transactions. Analytical Report. Flash Eurobarometer 320 (2010) <http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/flash/fl_320_sum_en.pdf> (visited May 19, 2012). |

| [xvii] B2C survey, supra note 16, at 19. In this context it should be noted that the B2C survey was developed for and directed at only businesses and only for/at those businesses which are already engaged in cross-border trading and those which despite having an interest in cross-border trade are not yet engaged in trading beyond national borders. Other businesses as well as consumers were not approached in that survey; Id., at 4 and 5. See, however, TNS Opinion & Social, Consumer Protection in the Internal Market. Special Eurobarometer 252 / Wave 65.1 (2006), chapter 3.2 <http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/archives/ebs/ebs252_en.pdf> (visited May 19, 2012) or The European Opinion Research Group EEIG and EOS Gallup Europe, Public Opinion in Europe: Views on Business-to-Consumer Cross-border Trade. Report B. Standard Eurobarometer 57.2 / Flash Eurobarometer 128 (2002), chapter II.1.1 <http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/archives/ebs/ebs_175_fl128_en.pdf> (visited May 19, 2012), two surveys directed at consumers. Both lead to substantially different results. For more details on the interrelationship of those three surveys and the likely consequences for the CESL see e.g. Wrbka, supra note 5, at 15-26. |

[xx] Viviane Reding, The Next Steps towards a European Contract Law for Businesses and Consumers, in Schulze & Stuyck, supra note 14, at 9, 10 (Munich: Sellier, 2011). |

[xxi] These three groups are in more detail defined by Article 2 (j), (k) and (m) Sales Law Regulation. Article 2 (k) Sales Law Regulation refers to sales contracts as “any contract[s] under which the trader (‘the seller’) transfers or undertakes to transfer the ownership of the goods [emphasis added] to another person (‘the buyer’), and the buyer pays or undertakes to pay the price thereof”. The only service contract element covered by the CESL is the group of “service[s] related to goods or digital content” (Art. 2 (m) Sales Law Regulation); thus, “unrelated” or free-standing service contracts would fall outside of the scope of application. |

[xxiv] For more examples see e.g. Recital 27 Sales Law Regulation. The Sales Law Regulation does not, however, give reasons why these areas were left untouched by the Proposal. It is indeed awkward, as questions of representation and/or legal capacity undeniably might also occur in B2C cases. Zimmermann tries to explain the lacunarity rather with the limited amount of time the Expert Group spent on drafting the proposal, argues that the draft is “in need of improvement” and asks for a “thorough examination and academic discussion” of the CESL draft; see Zimmermann, supra note 3, at 21. |

[xxv] See e.g. Micklitz, supra note 14, at 1811 or Zimmermann, supra note 3, at 21. |

[xxvi] The Centrum für Europäisches Privatrecht (or Centre for European Private Law) is located at the Universität Münster in Germany – see its website http://www.jura.uni-muenster.de/go/organisation/fakultaetsnahe-einrichtungen/cep.html for details (visited May 19, 2012). |

[xxvii] The Study Centre for Consumer Law is located in the Katholieke Universiteit Leuven in Belgium – see its website http://www.law.kuleuven.be/scr for details (visited May 19, 2012). |

[xxviii] For the conference draft see e.g. Schulze & Stuyck, supra note 14, at 217 (Munich: Sellier, 2011). |

[xxix] See also the first paragraph of the Standard Information Notice (i.e. Annex II of the Sales Law Regulation) which reads: “[t]he contract you are about to conclude will be governed by the Common European Sales Law … . These common rules are identical throughout the European Union, and have been designed to provide consumers with a high level of protection”. |

[xxxi] Zimmermann, supra note 3, at 16; see also Hans Schulte–Nölke, Der Blue Button kommt – Konturen einer neuen rechtlichen Infrastruktur für den Binnenmarkt, ZEuP 749, 755 (2011) who argues that “the consumer protection level recommended by the Expert Group is in total much higher than the consumer protection level of any Member State.” |

[xxxv] Art. 85 (a) states that a “contract term is presumed to be unfair for the purposes of this Section if its object or effect is to …restrict the evidence available to the consumer or impose on the consumer a burden of proof which should legally lie with the trader”. For another example, again from Austria, see e.g. the regulation on mistakes. Paragraph 871 ABGB (i.e. the Austrian Civil Code) says that “[i]f a party was mistaken with respect to the contents of a declaration given or received by him, and this mistake affects the essence or the fundamental nature of that to which the intention of the declaration was principally directed and expressed, no duties arise therefrom for the mistaken party, provided that this mistake was … promptly explained to him [note: the other party, i.e. the party which was not mistaken]”, the Common European Sales Law does not know an equivalent to this. |

[xxxviii] See e.g. Whittaker, supra note 4; Rühl, supra note 4; Hesselink, supra note 4; Roth, supra note 4; while the terms “2nd regime” and “28th regime” are of comparatively recent origin in this context, the substantial debate was not launched by the draft CESL; Heiss and Downes discussed this issue already in 2005, years before the Expert Group even started with its elaborations on the CESL – see Heiss and Downes, supra note 6. One can find also other concepts discussed in the legal literature. Rühl, for example, favours the form of “a uniform law that defines its own scope of application and that will accordingly apply if the parties validly agree” and calls it a “1st regime-model” – see Rühl, supra note 4, at 12. According to this view one could easily circumvent Rome I by opting for indepent applicability rules within the new sales law regime, which would explicitly exclude the application of the pertinent Rome I rules. The Max Planck Institute for Comparative and International Private Law (hereinafter, MPI), supra note 3, at 400-2, argues similarily by stating that “it seems preferable to adopt the approach considered in Art. 22(b) of the Rome I Proposal: the choice of the optional instrument ought to be exempted from the provisions of the Rome I Regulation” and that “[t]he issue should rather be dealt with by a set of specific rules that supersede, as leges speciales, the Rome I Regulation.” The MPI links its arguments to Recital 14 Rome I, which reads “[s]hould the Community adopt, in an appropriate legal instrument, rules of substantive contract law, including standard terms and conditions, such instrument may provide that the parties may choose to apply those rules” and gets support from Matthias Weller, who argues that “Recital 14 seems to indicate that a choice-of-law provision in this instrument allowing the parties to choose its rules as the applicable contract law will have priority under Article 23 [Rome I]” – see Matthias Weller, in Calliess, supra note 42, at Art. 23 Rome I Recital 7. (For details on Recital 14 Rome I see also Hein, id., at Art. 3 Rom I-VO Recital 58; or Rühl, supra note 4, at 5.) Such a 1st regime could actually render the protective regime of Art. 6 Rome I totally ineffective and, unless it would be considered as incompatible with the public policy (“ordre public”) of more protective Member States, it would more or less signify the end for a more ambitious consumer protection chosen by individual Member States. One must, however, also understand that the 1st regime model is “only” a recommendation by several commentators and that it stands in clear contrast to the actual draft wording of the CESL (which might be explained with the fact that many of the 1st regime voices were raised and reported to the Expert Group before the current CESL draft was published, even if they were published thereafter). The Commission makes it very clear that – for the time being – it would not follow the 1st regime; Recital 10 Sales Law Regulation reads that “[t]he agreement to use the Common European Sales Law should be a choice exercised within the scope of the respective national law which is applicable pursuant to Regulation (EC) No 593/2008 [i.e. Rome I]. … This Regulation [i.e. the Sales Law Regulation] will therefore not affect any of the existing conflict of law rules.” In its Explanatory Memorandum the Commission further states that “[t]he Rome I Regulation … will continue to apply and will be unaffected by the proposal. …The Common European Sales Law will be a second contract law regime within the national law of each Member State”. Rühl, one of the supporters of the 1st regime who commented on the CESL draft after its publication, has to admit that “[i]t follows that the European Commission wants to apply the CESL only if the rules of private international law, notably the rules of the Rome I-Regulation, call for application of the law of a member state.” – Rühl, supra note 4, at 8. Thus, there is no indication that the 1st regime model would currently be of further importance, at least not for this paper if one assumes that the CESL will be enacted without bigger changes. |

[xl] Id. at 8-9, coming to the conclusion that the CESL should be “regarded as sui generis”. |

[xlii] See for example the extensive list of literature listed in id, at 4, FN 12. For more details on this issue see e.g. Gralf-Peter Calliess, in Gralf-Peter Calliess (ed.), Rome Regulations Art. 3 Rome I Recitals 20 et seq. (Alphen aan den Rijn: Kluwer Law International, 2011) or Jan von Hein, in Thomas Rauscher (ed.), Europäisches Zivilprozess- und Kollisionsrecht EuZPR / EuIPR Art. 3 Rom I-VO Recitals 49 et seq. (Munich: Sellier, 2011). |

[xliii] See e.g. Calliess, supra note 42, at Art. 3 Rome I Recital 21; Hein, supra note 42, at Art. 3 Rom I-VO Recital 54; Francisco J. Garcimartín Alférez, The Rome I Regulation: Much Ado About Nothing?, 2-2008 The European Legal Forum 61, 67 (2008). |

[xliv] See European Commission, supra note 15, at 2 and chapter 2.2 of this paper. |

[xlv] See e.g. Staudenmayer, supra note 4, at 1494-5 or Hesselink, supra note 6, at 3. |

[xlvi] See e.g. Staudenmayer, id. or Hesselink, id.; Micklitz and Reich, two more neutral commentators conclude that the CESL would eventually lead to “full harmonisation within its scope” – see Micklitz & Reich, supra note 5, at 22; but see also chapter 4 of this paper for a discussion of the relationship between the CESL and Article 6 Rome I. |

[xlvii] Martijin W. Hesselink, a member of the Study Group and thus co-drafter of the CESL, goes in the same direction and tries to resolve the academic debate of categorizing the CESL either as a 2nd or 28th regime, by referring to the CESL as a “hybrid” or a “sui generis legal order”, both referring to national laws (from the viewpoint of its application); see Hesselink, supra note 4, at 6 and 7. |

[xlviii] Council Regulation (EC) No 1435/2003 of 22 July 2003 on the Statute for a European Cooperative. |

[xlix] Council Regulation (EC) No 40/94 of 20 December 1993 on the Community trade mark OJ L 11. |

[li] The central provision in this regard it to be found in Art. 3 (1) Rome I: “A contract shall be governed by the law chosen by the parties.” For a more detailed explanation of the background of this principle see e.g. Calliess, supra note 42, at Art. 6 Rome I Recital 1 et seq. or Hein, supra note 42, at Recital 1 et seq. |

[liv] This issue is not clearly answered yet and has yet to be analyzed in detail in the literature at the time of writing this paper. |

[lvii] Jürgen Basedow, European Contract Law – The Case for a Growing Optional Instrument, in Schulze & Stuyck, supra note 14, 169, 169. |

[lviii] For more details on the preferential test see e.g. Calliess, supra note 42, at Art. 6 Rome I Recitals 67 et seq. or Bettina Heiderhoff, in Rauscher, supra note 42, at Article 6 Recitals 51-2. |

[lxii] Things would be different if one sees the CESL as a 28th regime, as that would not override mandatory national rules. However, as shown above, treating the CESL as a 2nd regime seems to be more logical. Consumers with their habitual residence in a Member State with a higher protective standard than the CESL would thus be put in a worse position. |

[lxiii] Stefan Leible, The Proposal for a Common European Sales Law – How Should It Function Within the Existing Legal Framework, 3, available at http://www.europarl.europa.eu/document/activities/cont/201203/20120307ATT40127/20120307ATT40127EN.pdf (visited May 19, 2012). |

[lxviii] For the Commission’s view on the issues of subsidiarity, proportionality and choice of instruments see e.g. European Commission, supra note 15, at 9-10. With regard to the chosen form as being the “lesser evil” the Commission argues that “[a] Directive or a Regulation replacing national laws with a non-optional European contract law would go too far as it would require domestic traders who do not want to sell across borders to bear costs which are not outweighed by the cost savings that only occur when cross-border transactions take place”; see id., at 10. |

[lxx] Green Paper from the Commission on policy options for progress towards a European Contract Law for consumers and businesses, July 1, 2010, COM(2010) 348 final. |